by Warren M. Sherk

When Classic FM named Red River as the Greatest Western Film Score last month it brought the name Frederick Herbert back onto our radar. Herbert is credited with the lyrics for the popular song “Settle Down” that figures prominently in the film. His lengthy career as a lyricist and music editor has largely been overlooked. Without a Wikipedia page to use as a starting point, it takes a bit of digging to unearth his story, which is quite interesting.

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

A historical drama rooted in betrayal based on a Thornton Wilder Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, brought composer Dimitri Tiomkin and lyricist Frederick Herbert together to work professionally on a movie for the first time in the fall of 1943. By now, Frederick Herbert was transitioning away from using the name Herb Stahlberg. Although his birth name had served him well for his first 34 years—the Stahlberg surname must have carried some caché in musical circles as his father, Frederick “Fritz” Stahlberg, had been a well-known and respected musician in New York and Hollywood—Herb Stahlberg felt that his German surname was holding him back in the strong Jewish presence of 1940s wartime Hollywood. More on that later. (To avoid confusion, we will use Frederick Herbert, his better-known professional name, throughout this article.)

Two songs, “Poor Poor Mama” and “The Devil Will Get You,” performed by actress Lynn Bari in The Bridge of San Luis Rey contain Frederick Herbert lyrics set to music by Tiomkin.

Confusion sets in immediately since the titles of those two songs as listed on the music cue sheet differ from three songs filed under the film in the Dimitri Tiomkin Collection at the University of Southern California’s Cinematic Arts Library.

“The Dimitri Tiomkin Collection: An Inventory of Music,” by Harvey R. Deneroff dating from 1981, accounts for the following song material.

- Original musical sketches by Dimitri Tiomkin, including conductor part for the song “The Crow and the Crown,” holograph. Also, miscellaneous orchestral parts for the latter, in hands of copyist Maurie Rubens.

- Holograph of lyrics to song “Mis Chicos,” by Frederick Herbert, for music by Tiomkin. Also ozalid masters, and holograph and ozalid orchestral parts for the song.

- Original musical sketches for song “Where is Love?” by Dimitri Tiomkin, holograph; ozalid masters, copies of holograph orchestral parts for song.

The book, Memorable Films of the Forties, by John Howard Reid lists four songs in total: “Songs (all [sung by Lynn] Bari): ‘Sad to be a Donkey’ ‘The Old Crow’; ‘Mi Chicos’; ‘What Is Love?’”

Further, the film review in Variety states, “Dimitri Tiomkin, musical director, also wrote in collaboration with Herbert Stollberg, three songs used—‘Mi Chicos,’ ‘What Is Love?’ and ‘The Marquesa’—none of which are catchy.” (Before he abandoned the Stahlberg surname entirely, during World War II Frederick Herbert used both Stollberg and Stolberg in an attempt to de-Germanize his name.)

Those same three song titles appear in the film’s pressbook. (Neither mention “Poor Poor Mama.”)

Dimitri Tiomkin and Herbert Stolberg wrote the three songs which are sung by Lynn Bari, star of the film. They are ‘Mi Chicos,’ a fast Peruvian dance, ‘What Is Love,’ which will be the theme song of the picture and ‘The Marquesa,’ a novelty number. Mr. Tiomkin, who is an outstanding musical director was responsible for the film’s entire score. He accomplished his job so successfully that Reynaldo Luza, Peru’s foremost artist who served as technical advisor on the picture appeared to be lulled to sleep during the recording of the numbers.

When Tiomkin, not considering Luza’s nodding a compliment, asked ‘How come,’ Luza hurriedly soothed any injured feelings by assuring Mr. Tiomkin that he wasn’t sleeping at all, but was merely day-dreaming of his native Peru.

From “The Bridge of San Luis Rey” in Cinema Press Books

To sort the songs out we turned to the MPAA/Production Code Administration (PCA) files housed at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library. Because song lyrics had to be submitted to the PCA as part of the process of obtaining an MPAA certificate, we can follow the paper trail.

On October 13, 1943, the office of the producer Benedict Bogeaus sent “four numbers which we intend using [sic] in the ‘Bridge of San Luis Rey.’” They are a Marquesa Song, “The Crow and the Crown” [short version] (1:55); a Street Song, “Where Is Love?” (1:22); a Fiesta Song, “Mi Chicas” (1:25); and Marquesa Song, “The Crow and the Crown” [long version] (2:40).

The PCA response the following day began, “We have read the lyrics…bearing in mind the possible reaction of Latin-American audiences, and are happy to report that they seem acceptable from this point of view.” The letter went on, however, “From the standpoint of correct grammar, in the Fiesta Song, the frequently used phrase, ‘Mi Chicos’ and ‘Mi Chicas,’ should correctly read ‘Mis Chicos’ and ‘Mis Chicas.’”

On November 8, 1943, lyrics for another song, “I Love Love,” are submitted. And a day later the lyrics for “Poor Poor Mama” are offered.

A viewing of the film streamed via Amazon Prime brings us full circle, Lynn Bari performs “Poor Poor Mama” (from approximately 7:05 to 8:00) and “The Devil Will Get You” (from approximately 56:05 to 57:30), the two songs on the cue sheet.

For those keeping track, a reading of the lyrics confirms that “Poor Poor Mama” contains the lyric “It’s Sad to Be a Donkey” and “The Devil Will Get You” is the Marquesa Song and is synonymous with “The Crow and the Crown”…except the lyric in the film is “The Devil Will Take Her.” The Street Song, “Where Is Love?” (also referred to as “What is Love”); Fiesta Song, “Mi Chicas”; and “I Love Love” are not heard.

However, there’s a catch. The AFI Catalog notes copyright records, and the Motion Picture Herald and Variety reviews list the film’s running time as 107 minutes, the Daily Variety review lists it as 90 minutes, the print viewed for the AFI Catalog entry was 87 minutes (Amazon Prime streaming clocks in at 88 minutes).

The Variety running time was based on a preview in New York on January 31, 1944. The film was released and copyrighted on February 11.

So, it’s entirely possible the musical numbers not heard, “Mi Chicos” and “Where/What Is Love?,” were cut from longer versions of the film.

Further, by her own admission, Lynn Bari did not sing one of the two songs that remain in the film. In Foxy Lady: The Authorized Biography of Lynn Bari by Jeff Gordon, in an interview the actress-singer recalls the circumstances of recording the music.

Dimitri Tiomkin, a very talented guy, did the music on it. I talk-sang [‘New Words to an Old Melody’] at the piano in the scene at the palace. Evidently, that’s how they did their poetry then. My other number was ‘The Donkey Song.’ We worked very hard on it. But, the day I was supposed to record, I lost my voice. I was sick for a few days and couldn’t open my yap. I don’t know if it was nerves; I’ve never quite been able to figure that one out. So they got some woman to record the song whose voice was nothing like mine.

“New Words to an Old Melody” does not match any of the lyrics of the four songs discussed.

Despite the critique of the songs in the Variety review, Tiomkin was nominated for an Academy Award for the music score.

But that’s not the end of the story…

In the summer of 1943, a few months before Bridge of San Luis Rey started production in mid-September, Tiomkin and Herbert embarked on a musical project centered around early California. In its first incarnation the operetta was titled, Milk and Honey. Later titles include Sweet Surrender and Old California.

The song list for Milk and Honey on a carbon typescript in the Tiomkin collection includes at least one song, “Caliente (aka Mi Chicos),” submitted to the PCA for Bridge of San Luis Rey.

(The history of Milk and Honey will be the subject of a future article.)

Before we delve further into the Tiomkin and Herbert film songography, let’s untangle the Stahlberg family history, beginning with Frederick William Stahlberg, the father, of Frederick Herbert Stahlberg, better known as Herb Stahlberg and Frederick Herbert.

Frederick William Stahlberg

Born Frederick William Stahlberg in 1877, in Ketzin, Prussia, in the Province (now state) of Brandenburg, Germany, Frederick Stahlberg received musical training in Stuttgart on the piano and violin and studied music theory. Coming to America in 1899, he played first violin under the German-raised conductor Victor Herbert with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Stahlberg’s uncle in Germany had been one of the “young bloods of Stuttgart” that counted Herbert among their number. Stahlberg himself made acquaintance with Herbert’s mother while living in Stuttgart and she recommended him to her son. Victor Herbert exerted a strong influence and would be a recurring presence in Frederick Stahlberg’s professional life, where he dropped Frederick in favor of “Fritz.” When Herbert left the Pittsburgh Symphony in 1904 to form his own orchestra, Stahlberg took a position the following year with the Philharmonic Society of New York—now known as the New York Philharmonic—playing violin. (To make ends meet, he waited tables during the summer of 1905 in area hotels.)

Back page of New York Philharmonic Society program, November 10-11, 1905, listing “Stahlberg, F.” under violins. New York Philharmonic archive at archives.nyphil.org.

Herbert championed Stahlberg’s music compositions in Pittsburgh and continued to do so in New York. Even as Stahlberg concertized with the Philharmonic, Victor Herbert placed music by Stahlberg on his concert at the Broadway Theater in 1907, and in 1908 Stahlberg served as assistant conductor at the same for a Herbert concert that included the premiere of a work by Stahlberg.

Now as a composer of symphonic works Stahlberg’s writing career continued to blossom in New York with the Philharmonic. The New York Philharmonic Archive contains programs for four works composed and conducted by Fritz Stahlberg and performed by the orchestra between 1909 and 1916. View the February 4, 1916 program. A New York Times news item announced that Stahlberg had ascended to assistant conductor of the orchestra.

“At yesterday’s concert the Philharmonic Society played for the first time in New York a new suite for orchestra by Fritz Stahlberg, until this season one of the first violins of the orchestra, and now its assistant conductor. Several of Mr. Stahlberg’s compositions have been played by the Phiharmonic in recent years.”

“Philharmonic Concert,” New York Times, February 5, 1916

He had served as assistant conductor in the spring of 1912 for a six-week concert tour with the Victor Herbert orchestra. Herbert chartered three railroad coaches and a dining car to move the fifty musicians and entourage in style around the South and Midwestern United States.

Stahlberg’s transition from the concert hall included a stint as musical director for “Her Regiment,” a Victor Herbert operetta that opened in New York in 1917, after which Stahlberg toured the country with the ensemble into 1918.

Known professionally as Fritz Stahlberg in both Pittsburgh and New York, he reverted to his birth name, Frederick, sometimes spelled Frederik, for the remainder of his career as a composer and conductor after an incident in Detroit at the height of World War I.

“Her Regiment” was not an outstanding success in New York [opened November 12, 1917 at the Broadhurst Theater and ran for only forty performances] but proved to be a great attraction on the road. When we played in Detroit the show received very good notices, but one paper spoke of the musical direction being in the hands of “Fritz” Stahlberg, adding in parentheses, (“what a moniker these days!”). A kind and patriotic management took the hint: the despised, rejected and familiar “Fritz” disappeared from their programs in favor of the more formal “Frederik.” [Not only that, but the spelling of his last name was de-teutinized to “Stalberg.”]

Mr. Herbert thought, too, that because of the times the change was a good idea, but out of habit he kept calling me “Fritz” against his will. And in the red-hot war days this correcting “Fritz” to “Fred” was sometimes embarrassing.”

Stahlberg quoted in Victor Herbert: A Theatrical Life by Neil Gould, p. 484-5.

The Detroit paper mentioned above has remained elusive.

After the war, Frederick Stahlberg made the move from the concert hall and stage to the screen. An opportunity arose when Erno Rapée resigned as the conductor of the Rivoli Theater in November 1919 and Stahlberg stepped in.

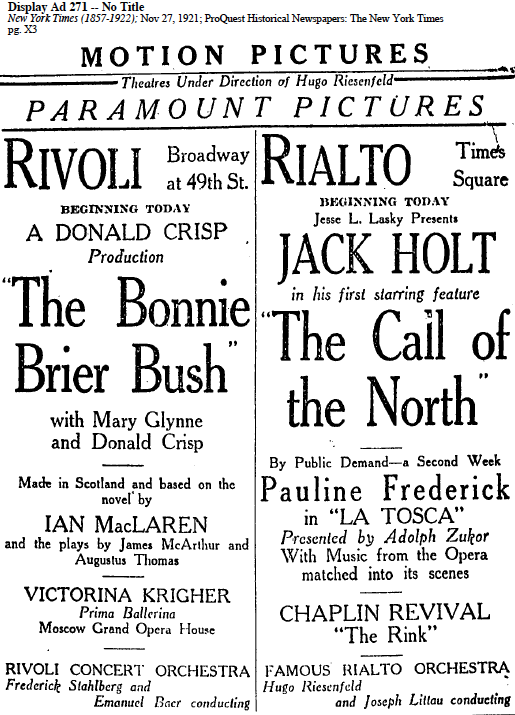

The Rivoli Theater, a cavernous movie palace seating more than 2,000 people, boasted a house orchestra, the Rivoli Concert Orchestra, that provided musical accompaniment for silent films and performed an ambitious musical program before and between screenings. Managing director Hugo Riesenfeld, one of the first composers to write original music for films, oversaw the theater’s music and Stahlberg was paired opposite conductor Joseph Littau to handle the arduous daily conducting chores. On the composing side, Stahlberg contributed additional music to a score by Reisenfeld for Deception (1921), before scoring A Woman of Paris (1923) on his own. Stahlberg stayed at the Rivoli through at least January 1923.

Victor Herbert came calling again and in August 1923, Stahlberg and Herbert led the 45-piece Cosmopolitan Theatre Orchestra as co-conductors. Stahlberg wrote a music score for the 1924 film, The Great White Way, presented by the Cosmopolitan Corporation. A month after the death of Victor Herbert in May 1924, Stahlberg was named music director of the theater. He is credited with a special arrangement for the Rialto Theater in February 1925 and remained at the Cosmopolitan Theatre through at least August of that year.

Both Victor Herbert and Stahlberg contributed compositions to the Carl Fischer Playhouse Series, one of three editions—concert, playhouse, and theatre—offered by the prodigious music publisher. The Playhouse Music Series for piano compiled into books selected mood pieces for motion pictures written in a playable manner for the average pianist.

When he signed on in December 1926 as one of four orchestra directors for the Roxy Theatre then under construction in New York, Stahlberg was in exulted company. He would work under a system of rotation alongside H. Maurice Jacquet, Charles Previn, and Erno Rapée, each “widely known for his work either in the motion picture theatre or symphonic fields.”

Roxy’s Gang, left to right, Leo Staats, Erno Rapee (seated), Frederik Stahlberg, Maurice Jacquet, Charles Previn, and “Roxy” Rothafel (seated), from “Roxy: A History,” Film Daily, 1927, page 2. The short-lived Gang at most performed together once, on opening night of the Roxy Theatre. Before the end of March 1927 both Stahlberg and Jacquet had left.

“The grand opening of the Roxy Theatre was the high water mark of the golden age of the American motion picture palace,” writes Donald L. Miller in Supreme City: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America. Eschewing the word “palace” and its royal connotation, local newspaper ads for the 6,200 seat movie theater branded it “The Cathedral of the Motion Picture” suggesting instead a religious association. Miller’s book recounts the opening night in some detail; however, it does not mention an item that appeared in Variety days later.

The trade publication reported that Stahlberg “walked out on opening night following a clash with his associates.” Did he walk before, during, or after the performance?

According to the Premiere Performance program, all four conductors were to participate in Jacquet’s symphonic tone poem, “Dedication” and Stahlberg was to solo conduct the first performance of Irving Berlin’s “A Russian Lullaby.” One would think that there would be a first-hand account of the Berlin premiere mentioning who was at the conductor podium, but alas, none has surfaced.

Three nights before the Roxy’s gala opening on March 11, when Roxy presented Jacquet, Previn, and Stahlberg on a “Roxy and His Gang” radio program Rapée was absent through illness. A behind-the-scenes account of the evening noted the “nervous tension” that resulted when Roxy “snatched the baton from the conductor and directed the orchestra and chorus himself. He also conducted when the Scotch band came on the air; in fact, ‘Roxy’ held the baton most of the time.”

We may never know the details of the subsequent opening night clash. Was it with Rapée, who Stahlberg replaced at the Rivoli at the beginning of his film conducting career? Miller describes Rapée as a “rigidly formal Hungarian conductor.”

It’s interesting to note that in pre-opening publicity the four conductors were named as equals, but as soon as Stahlberg walked, Rapée was named director of music and continued as one of now three conductors with Jacquet and Previn. This according to the Dedicatory Program for the week beginning March 19. Before the month was over Jacquet would resign. Stahlberg had already been replaced by Maximilian Pilzer who moved over to the Roxy from the Rialto.

Coincidently, on March 19, a Stahlberg concert work was performed by the Sunday Symphonic Society in New York.

It was the Roaring ‘20s and it didn’t take long for other opportunities to materialize. Stahlberg accompanied theater owner and showman Sid Grauman to Los Angeles from New York in July 1927. The previous month, Stahlberg led the orchestra of Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Los Angeles, after Constantin Bakaleinikoff moved over to the Egyptian Theater. In August, Stahlberg was off to Salzburg, Austria to conduct the European premiere of Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings, having directed performances at both the Gaiety Theater in New York and the Chinese Theater in Los Angeles.

After his Symphony in E Minor was awarded third prize in the American section of the International Schubert Contest in 1928 it seems his concert composing career went dormant.

Silent films were on their way out and synchronized music scores were in their infancy. Stahlberg and Josiah Zuro were the composer-arranger-conductors for film scoring and synchronization for RCA Photophone during the summer of 1928. RCA Photophone started nipping away at Fox’s Movietone and Warner’s Vitaphone.

That same year Stahlberg worked on a compiled score for the film Lilac Time, that is credited to Nathaniel Shilkret who penned the film’s popular theme song, “Jeannine, I Dream of Lilac Time,” with words by L. Wolfe Gilbert. In his autobiography Shilkret recalls,

“One of my first scorings was for a film called Lilac Time [1928], and it starred Gary Cooper and Colleen Moore. I was more interested in the theme song than in scoring the picture. In fact, all I wrote was my song Jeannine. I developed it in many moods and let a composer-musician fill the rest of the film with printed music. This was a time when publishers printed lots of mood music.”

The “composer-musician” filling in the score was Frederick Stahlberg, who also wrote or compiled additional music for three films with scores by William Axt during the same year.

Axt may have played a role in bringing Stahlberg to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), as he was already at the Culver City studio in September 1929 when Stahlberg signed on to conduct motion picture music.

Dimitri Tiomkin also signed with MGM in the fall of 1929 and it’s conceivable that they crossed paths at the studio. An ad in Variety in 1930 depicts Dimitri Tiomkin adjacent to a list of MGM conductors that includes Stahlberg.

“The Power Behind Great Song Hits,” advertisement for Robbins-Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Variety, April 9, 1930, page 33

That same month Variety reported, “According to Dimitri Tiomkin, ‘while New York is the musical heart of America, Hollywood has this year become its music soul.’”

The musical boom in Hollywood went bust before the end of the year and MGM released many conductors and composers from contract, including both Axt and Stahlberg.

Stahlberg, according to modern sources, worked on both Tarzan the Ape Man (MGM, 1932) and Tarzan and His Mate (MGM, 1934) with Paul Marquardt one of Tiomkin’s key orchestrators in later years.

“Dear Old New York Town,” a nostalgic song copyrighted in Los Angeles by Frederik Fritz Stahlberg, on June 15, 1937, apparently was his last musical composition. He died a week earlier on June 7.

At the time of his death, Frederick Stahlberg’s son was already working Hollywood, making him one of the first second-generation film industry professionals in America.

Frederick Herbert Stahlberg, also known as Herb Stahlberg and Frederick Herbert

Frederick Herbert Stahlberg was born in New York on June 4, 1909. His middle name honored Victor Herbert, his father’s mentor and friend. Perhaps because his father was also named Frederick, the younger Stahlberg became known as Herb.

Frederick Herbert would have been twenty-years-old when his father signed with MGM in 1929.

He found work in the Fox music department—his starting date is unclear—supplying lyrics for the Fox film, “Redheads on Parade” in 1935.

The year after the death of his father in 1937, Frederick Herbert married Francis Hill. By this time, at Fox he served as music editor for a Men’s Golf Tournament short film and could be seen golfing at the public Rancho course adjacent to the studio. (Today it is the City of Los Angeles’ Rancho Park Golf Course.) He would continue to work both as a music editor and lyricist for the remainder of his life.

During World War II his draft registration indicates he was employed by Song-o-Graph Productions in the fall of 1940. Song-o-Graphs appeared with other filmed musical shorts on “Panoram” jukeboxes made by the Soundies Distributing Corporation of America beginning in 1940. The lyrics he wrote for two songs with Rudy Schrager in 1940, “Way Down Deep” and “Better Look Out,” may have been for Song-o-Graph.

Before the war was over Dimitri Tiomkin met Frederick Herbert. They would go on to collaborate on songs for five films, including The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Whistle Stop, Duel in the Sun, It’s a Wonderful Life, and Red River.

READ: Part 2: The film songs of Dimitri Tiomkin and Frederick Herbert

Sources

The Bridge of San Luis Rey

- Universal Terrors, 1951-1955: Eight Classic Horror and Science Fiction Films, by Tom Weaver, Robert J Kiss, Steve Kronenberg, David Schecter, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017. Quote in book reads, “…as he felt that his German surname was holding him back in the strong Jewish presence of postwar Hollywood.”

- “The Dimitri Tiomkin Collection: An Inventory of Music,” by Harvey R. Deneroff, University of Southern California Cinematic Arts Library, 1981

- Memorable Films of the Forties, by John Howard Reid, Lulu Press, 2004

- “The Bridge of San Luis Rey” in Cinema Press Books [New York Public Library], on microfilm reel 2, consulted at the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- “The Bridge of San Luis Rey,” Motion Picture Association of America. Production Code Administration records, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- The Bridge of San Luis Rey, streamed via Amazon Prime on May 11, 2018

- The Bridge of San Luis Rey, AFI Catalog, catalog.afi.com, consulted May 2018

- Foxy Lady: The Authorized Biography of Lynn Bari by Jeff Gordon, Duncan, Oklahoma: BearManor Media, 2010

Frederick William Stahlberg

- “Stahlberg, Frederick,” in the Encyclopedia of Biography, New Series, Volume 9, 1938, p. 312

- Program 1905 Nov 10, 11 / Subscription Season / Mengelberg (ID: 6438), in Programs > 1915-16 Season > Subscription Season, New York Philharmonic archive, archives.nyphil.org, consulted May 26, 2018

- Program 1916 Feb 04 / Subscription Season / Stransky (ID: 7172), in Programs > 1915-16 Season > Subscription Season, New York Philharmonic archive, archives.nyphil.org, consulted May 26, 2018

- Victor Herbert: The Biography of America’s Greatest Composer of Romantic Music by Joseph Kate, New York: G. Howard Watt, 1931

- Victor Herbert: A Theatrical Life by Neil Gould, New York: Fordham University Press, 2008 [on Stahlberg’s first meeting/interview with Herbert, quoting from “Yesterthoughts,” by Frederik Stahlberg, unpublished memoir of Victor Herbert, Yale University Music Library]

- “Music for the Photoplay” Exhibitors Trade Review, Vol. 10, No. 26, November 26, 1921

- “Musical Comedy and Motion Pictures,” Musical Courier, August 10, 1922

- Ad for Rialto Theater in Racine, Wisconsin in Racine Journal-News, April 21, 1924

- Ad for Varsity Theatre in Lawrence, Kansas in Lawrence Daily Journal-World, May 14, 1924

- “Four Directors Are Signed for New Roxy,” Exhibitors Herald, December 25, 1926

- “Roxy Theater Musical Staff Completed—Rapee Engaged,” The Billboard, January 1, 1927

- “Maestro, Jumping About Like a Grasshopper, Holds The Baton During Most of the Concert—Nervous Tension Among the ‘Gang,’” New York Times, March 13, 1927

- “Stahlberg Walks on Roxy,” Variety, March 16, 1927

- American Showman: Samuel Roxy Rothafel and the Birth of the Entertainment Industry, 1908–1935 by Ross Melnick [on the opening of the Roxy Theatre and Carl Fischer Playhose Series]

- “Pilzer Joins Roxy,” Film Daily, March 29, 1927

- “Prize Is Awarded in Schubert Contest,” Hamilton Daily News, Hamilton, Ohio, May 16, 1928

- “Survey of Photophone Situation for Kennedy’s Affiliations,” Variety, June 27, 1928, page 19

- “Along the Coast,” by Bill Swigart, Variety, September 18, 1929 [on the signing of Stahlberg with MGM]

- “Hollywood Melody Makers,” Motion Picture News, September 21, 1929

- “Songs of Hollywood,” Exhibitors Herald-World, September 28, 1929 [Frederick Stahlberg signed by MGM]

- “The Power Behind Great Song Hits,” advertisement for Robbins-Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Variety, April 9, 1930, page 33

- “M-G-M Lets Out Music Staff at Coast Studios,” Motion Picture News, Vol. XLII, No. 19, November 8, 1930: 26

- Catalog of Copyright Entries, Third Series, Library of Congress [song, “Better Look Out”]

- “Stahlberg, Leader of Music for Films” [obituary], New York Times, July 24, 1937

Frederick Herbert Stahlberg

- 20th Century Fox Close-Ups (1937-1938) [on golfing]

- Universal Terrors, 1951-1955: Eight Classic Horror and Science Fiction Films, by Tom Weaver, Robert J Kiss, Steve Kronenberg, David Schecter, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017. See especially page 354.

- U.S. World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940–1947, Frederick Herbert Stahlberg, October 16, 1940, accessed at ancestry.com

Name Thesaurus

Birth name: Frederick William Stahlberg

Professional names: Fritz Stahlberg, Frederick Stahlberg, Frederik Stahlberg, Frederik Fritz Stahlberg

Birth name: Frederick Herbert Stahlberg

Professional names: Herb Stahlberg, Herbert Stolberg, Herbert Stollberg, Frederick Herbert